Notes and Knowledge Management

Tl;DR

Pros and Cons of few note taking apps.

While learning which markdown edition fwks for notes are available for my future SaaS.

+++ quick selfhosting guide in the conclusions

+++ Understanding why I cant use TinyAuth infront of nextcloud android App

Intro

For me this blog is my current way of storing knowledge and a historical track of my tech learning.

But how people do this in a PRO and private way?

sudo snap install joplin-desktopWith notes as in many other topics, it seems that all comes down to: just markdown (vs) more features and ,locking'

Knowledge Management Tools

These are some knowledge management tools, noting their data storage method:

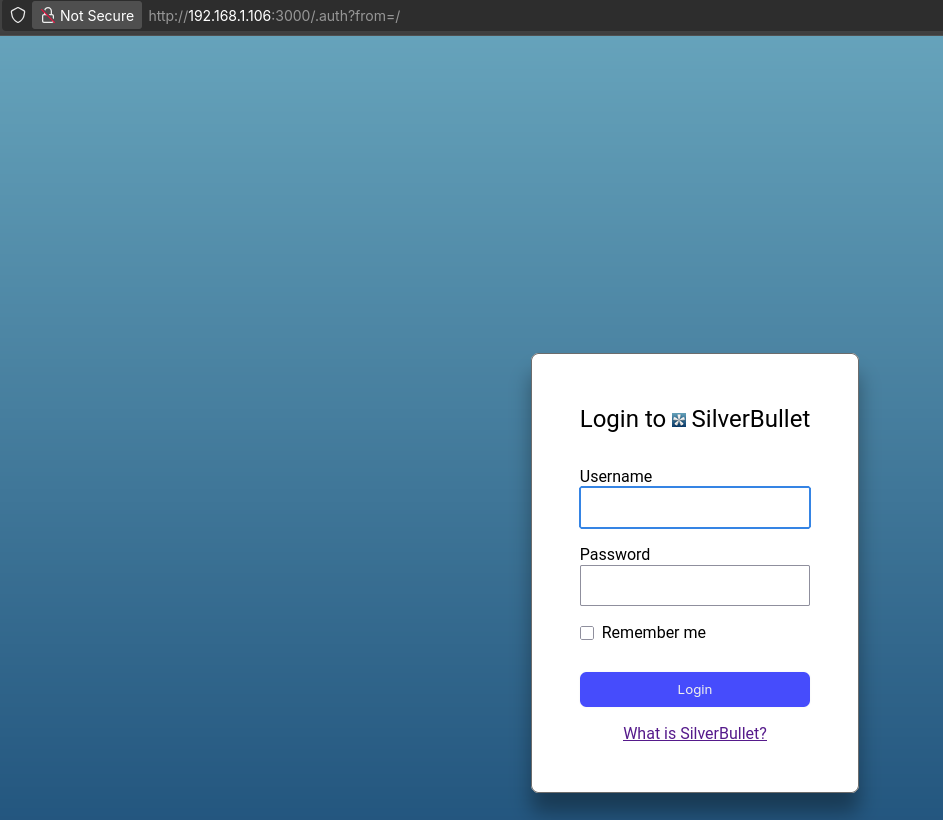

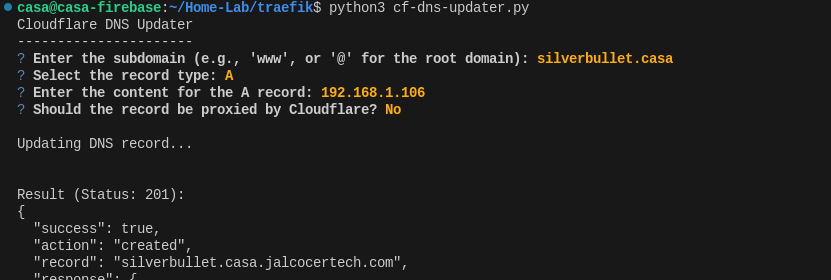

- SilverBullet: A web-based “second brain” tool that stores its Markdown notes as flat files locally or on a self-hosted server, emphasizing extensibility and linking.

- Joplin: A feature-rich, open-source note-taking and to-do app that uses a database (SQLite by default, or other databases via sync targets) to store notes, with robust Markdown support and synchronization.

- Logseq: An open-source, local-first knowledge base and outliner that stores its content as Markdown or Org-mode flat files directly on your filesystem, focusing on bi-directional linking and block-based editing.

- BookStack: A user-friendly, self-hosted platform ideal for organizing documentation and wikis, relying on a database (MySQL/MariaDB) to manage its structured content.

- Raneto: A simple, flat-file Markdown knowledge base built with Node.js, requiring no database and storing all content as simple Markdown files.

The core of the “privacy and control” movement in note-taking apps.

The answer is that there’s a spectrum, but many of the popular self-hostable options do not follow the same “plain text files” model as Logseq.

Among your options and other popular apps, the following are truly “flat notes” apps for self-hosting or desktop use—they save each note as an individual Markdown file, without any enforced hierarchical folder structure:

- Fully Flat Notes Apps

Flatnotes: Stores notes as markdown files in a single flat directory—no folders or notebooks. This keeps things simple, and the note files are portable and directly accessible as plain Markdown.

Raneto: Organizes its knowledge base with Markdown files, which are stored as flat files on disk (although notes can be grouped in folders physically, the system just reads everything as files; no database is used).

- Mostly Flat, Hierarchy Optional or Supported

- SilverBullet: Stores Markdown notes as flat files; folder hierarchies can be used but are not required or mandatory. The core is file-based, with high customization, and is considered a flat-file “second brain”.[4]

- Logseq: Mainly keeps notes as flat Markdown or Org-mode files on your filesystem. Hierarchical linking and block referencing are possible, but each “page” is essentially a flat file. With Android app.

- Not Flat-File (Uses Database or Enforces Hierarchy)

- Joplin: Uses SQLite (by default) to store and index notes, even if notes are written in Markdown. Sync may export files, but core operation is database-driven, not flat files.[1]

- BookStack: Organizes notes in a strict hierarchy (Books, Chapters, Pages) and stores content in a MySQL/MariaDB database, not as accessible flat Markdown files.[1]

The “Plain Text” Philosophy vs. “Database” Philosophy

- Logseq, Obsidian, and others are built on the “plain text” philosophy. Their primary goal is to ensure that your notes are always a collection of human-readable Markdown files that you can access and read with any text editor, even if the app itself is no longer around.

This makes your data highly portable and future-proof.

- Pros: Ultimate data portability, easy backups, works great with file-syncing tools like Syncthing.

- Cons: Not all features (like an embedded database for fast search or complex queries) are as easy to implement and can sometimes lead to performance issues with very large graphs.

Some people use obsidian + HUGO: https://www.nickgracilla.com/posts/obsidian-is-my-hugo-cms/

- Joplin, Memos, and others often use an “app-specific database” philosophy. While the notes themselves are written in Markdown, they are stored in a database (like SQLite, PostgreSQL, etc.) on the device and on the server. The apps then use a synchronization protocol to keep these databases in sync.

- Pros: Can offer very fast and powerful search, more robust conflict resolution, and support for features like multi-user collaboration and sharing.

- Cons: The data is not as easily accessible or human-readable outside of the app. If you were to lose the app, you would have to figure out how to export or convert the database to get your notes back. Your data is not “future-proofed” in the same way as plain Markdown files.

A Deeper Look at Joplin

Joplin is a perfect example of this.

It’s an open-source, self-hostable, and privacy-focused note-taking app that many people love.

And you can create themes for Joplin: https://github.com/manuelernestog/joplin-minimalist-light-theme

However, its core philosophy on file storage is different from Logseq’s.

How it works: Joplin stores your notes, attachments, and metadata in a single SQLite database file on your desktop and mobile devices.

The Sync Process: When you sync, the app does not simply sync a folder of Markdown files. Instead, it pushes the changes from its local database to a remote location (your Nextcloud, WebDAV server, Dropbox, etc.). This sync location contains a special set of files that represent the state of the database, not your individual notes. The other clients then pull these changes and update their local databases.

Android App: Joplin has excellent, native Android and iOS apps. They are built to work with this database-driven sync model, so you don’t need a separate app like FolderSync. You just configure the app with your sync target’s URL and credentials, and it handles the rest.

Self-Hosting: Joplin offers a self-hostable Joplin Server that you can run in a Docker container. This server is a dedicated sync endpoint that makes it very easy for all your Joplin clients to connect and sync with.

It’s a much more “turnkey” solution for self-hosting than piecing together a file-syncing solution.

Other Self-Hostable Options

Memos: This is another popular self-hosted app. Like Joplin, it stores all its data in a database (e.g., SQLite, MySQL, or PostgreSQL). The front-end is a web app, and there are unofficial mobile clients, but the core data is in a database, not a flat file system.

Trilium Notes: This is a very powerful and feature-rich app that stores all data in a single SQLite file. This makes it easy to back up but doesn’t follow the flat Markdown file model.

FlatNotes: This app is an interesting exception that follows the same philosophy as Logseq. It’s a “database-less” web app that uses a flat folder of Markdown files for storage. It’s designed for simplicity and portability.

The Verdict

If your primary goal is to have human-readable Markdown files that are independent of any specific app, and you prefer a file-system-based workflow, then Logseq (or a similar tool like Obsidian) is a better choice. The sync solution will be external to the app itself (e.g., Syncthing, Nextcloud).

If your priority is a seamless, self-hosted sync experience with native mobile apps, and you’re comfortable with your data being stored in a database, then Joplin is an excellent choice. Its self-hosted server makes the setup straightforward, and the native mobile app “just works” with that server.

Conclusions

To edit collaboratively, see https://github.com/ether/etherpad-lite

Apache v2 | Etherpad: A modern really-real-time collaborative document editor.

Or: https://rustpad.io/ at https://github.com/ekzhang/rustpad

Efficient and minimal collaborative code editor, self-hosted, no database required

Rustpad is an open-source collaborative text editor based on the operational transformation algorithm.

Share a link to this pad with others, and they can edit from their browser while seeing your changes in real time.

Built using Rust and TypeScript. See the GitHub repository for details.

If you are looking for simplicity, have a look to the flat file and local first options, like raneto or:

You might also be thinking…how about using those to provide SSG editor capabilities

Kind of a ~ flatfile CMS?

| App | Flat Files | Pure Markdown | No DB | Hierarchy-Free |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flatnotes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Raneto | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (or folders, optional) |

| SilverBullet | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (folders optional) |

| Logseq | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (folders/pages possible) |

| Joplin | No | Yes | No | No |

| BookStack | No | No | No | No |

Flatnotes, Raneto, SilverBullet, and Logseq are the best picks if flat, human-readable Markdown files with no database lock-in are the priority.

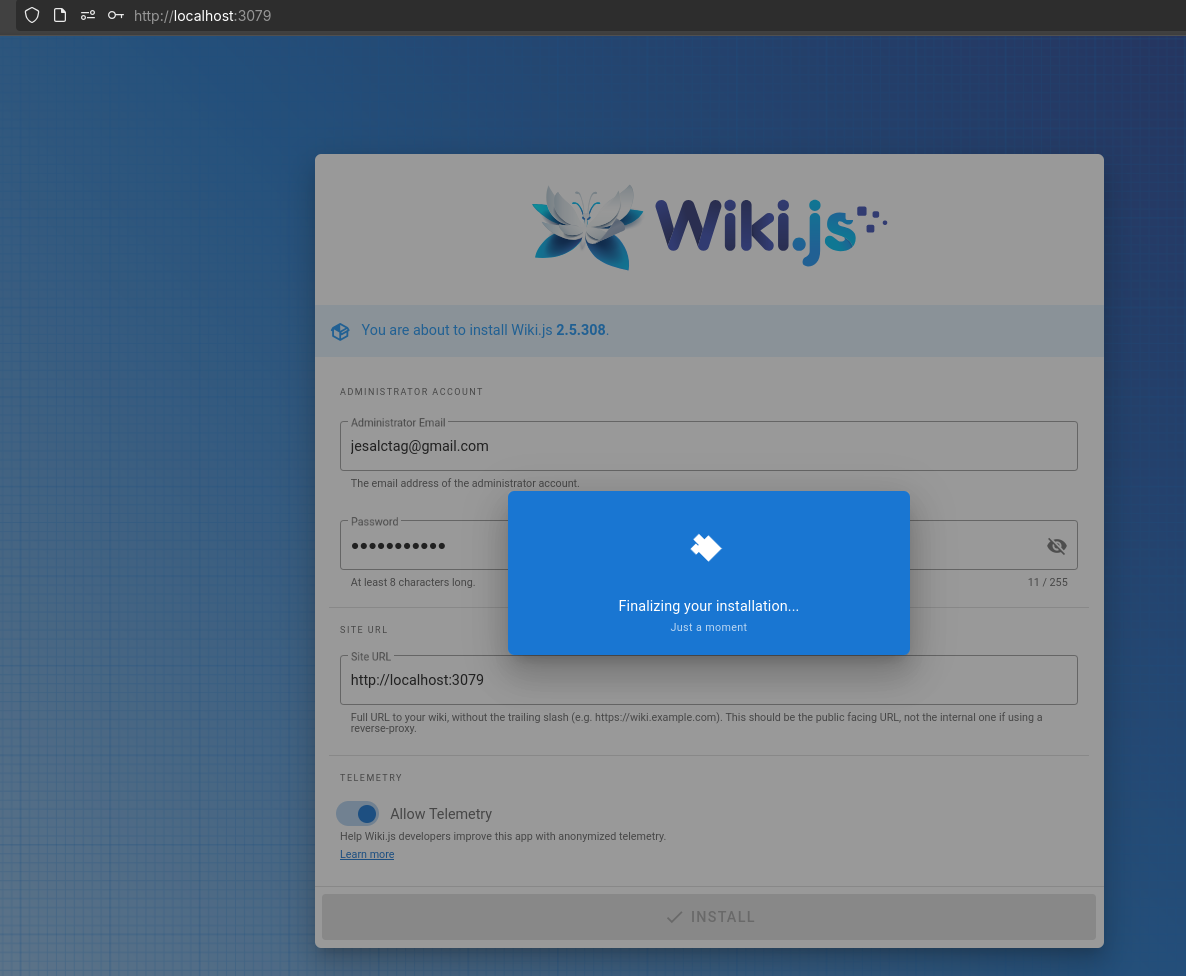

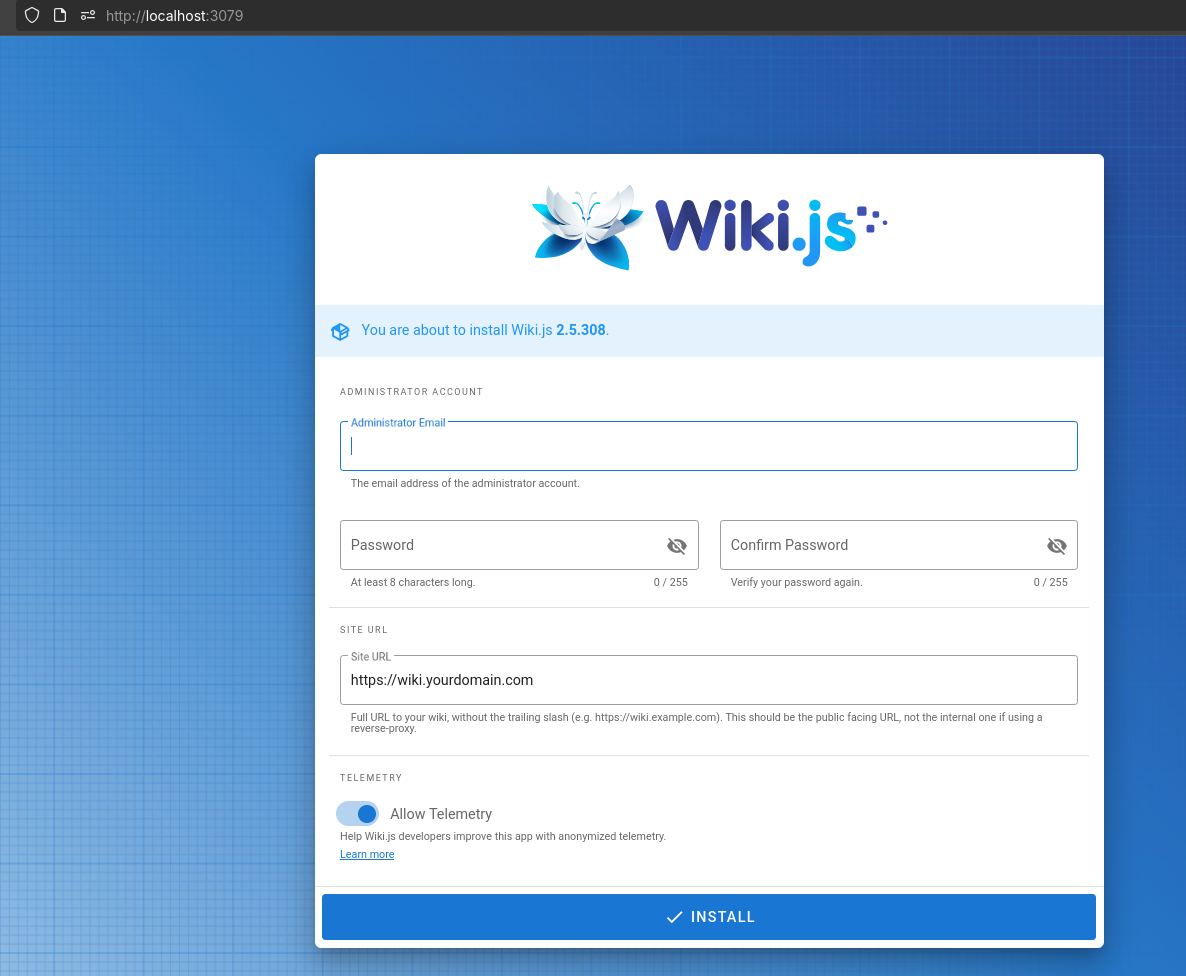

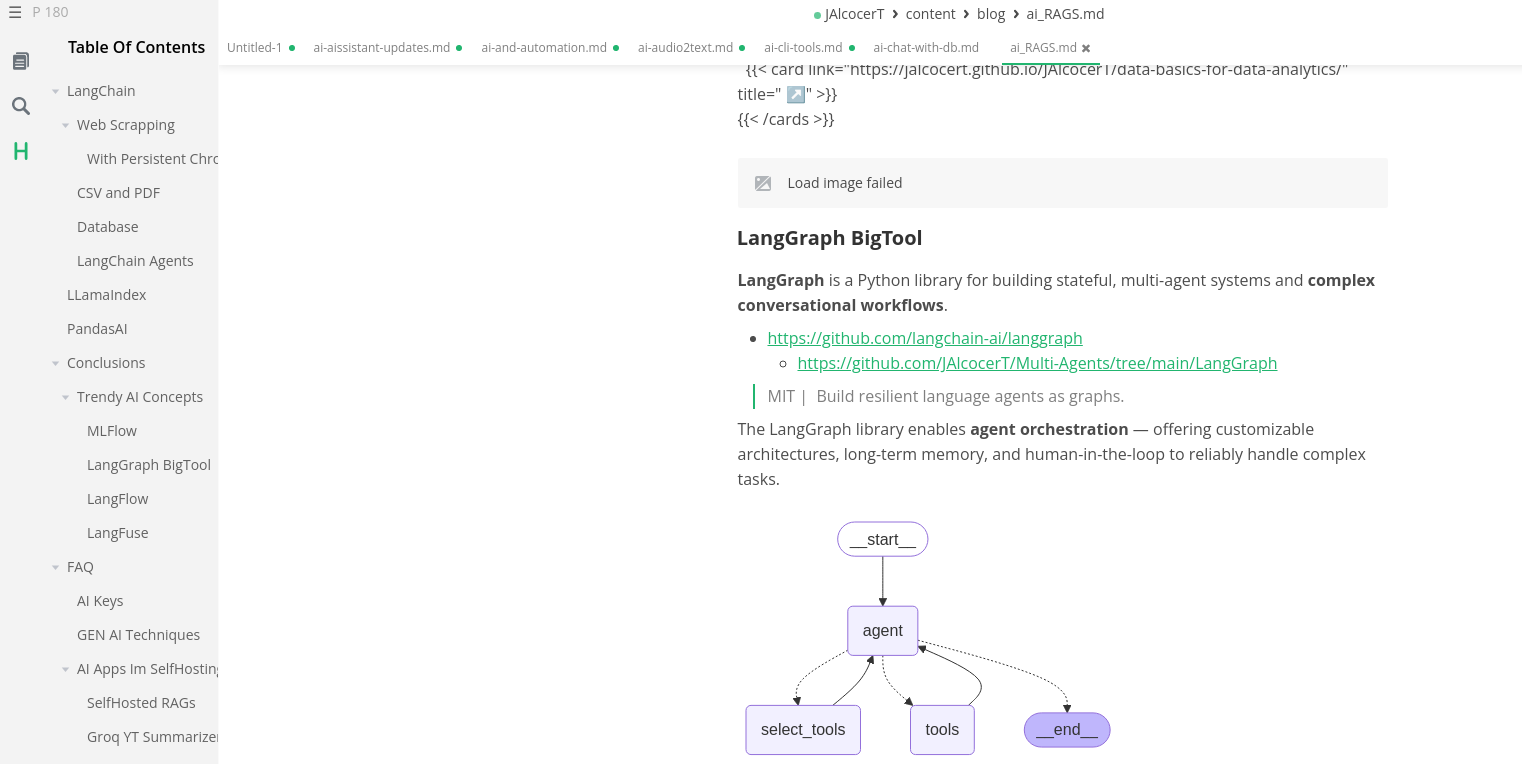

About WikiJS

I know what you are looking for: DATABASE-LESS KNOWLEDGE BASE

- https://docs.linuxserver.io/images/docker-raneto/#miscellaneous-options

- https://docs.linuxserver.io/images/docker-hedgedoc/

- https://js.wiki/

And then, just login to wikiJS:

See also:

The Markdown-based note-taking app that doesn’t suck.

A lightweight note-taking application that lets your thoughts flow naturally while keeping your tasks in check. NoteFlow transforms a single Markdown file into a modern web interface where notes and tasks coexist seamlessly.

A simple, markdown-based note-taking application written in python and built with NiceGUI.

Quick SelfHosting Resources for Notes

Some other places Ive been putting together notes config:

MIT | A minimalistic wiki powered by python, markdown and git.

FAQ

The Logseq Android app stores its notes as local plain-text Markdown files on your phone.

This is a core design principle of Logseq, which is to prioritize user privacy and control by keeping your data on your own device.

Regarding syncing with a server, there are a few options, and this is where it gets a bit more involved:

Official Logseq Sync: Logseq offers its own paid sync service. This is the most straightforward way to sync your notes across your desktop and mobile devices. It’s designed to handle conflicts and keep your notes up-to-date automatically. You typically set up the first remote graph on the desktop app, and then connect your mobile app to it.

Third-Party Sync Services: Because Logseq uses local Markdown files, you can use third-party file synchronization services to sync your graph folder. Popular choices include:

- Syncthing: This is a free, open-source, peer-to-peer file synchronization tool. It’s highly recommended by many Logseq users for its fast and reliable syncing without a central server. You would install Syncthing on all your devices (phone, desktop, etc.) and configure it to sync your Logseq folder.

- Cloud storage services: You can use services like Google Drive, Dropbox, or OneDrive. You would need to use a third-party app on your Android device (like FolderSync or a similar app) to automatically sync your Logseq folder with the cloud storage folder.

Self-Hosting a Web App: Deploying Logseq as a web application on your own server is possible using technologies like Docker. However, it’s important to note a few things about this approach:

- Local Storage Limitation: Traditionally, the web app version of Logseq relies on the browser’s File System Access API, which means it still stores the files locally on the device you are using the browser on. This makes it difficult to have a single, server-side source of truth for your notes.

- Workarounds: Some users have found workarounds, often involving running Logseq in a Docker container and using a mounted volume to store the notes on the server’s file system. This allows for a more centralized setup, but it can be technically complex to set up and manage, and some features like plugins might not be fully supported.

In summary, the Logseq Android app stores your notes locally.

While you can deploy a self-hosted web app, the easiest and most common ways to sync your notes with a server are either through the official Logseq Sync service or by using a third-party file synchronization tool like Syncthing.

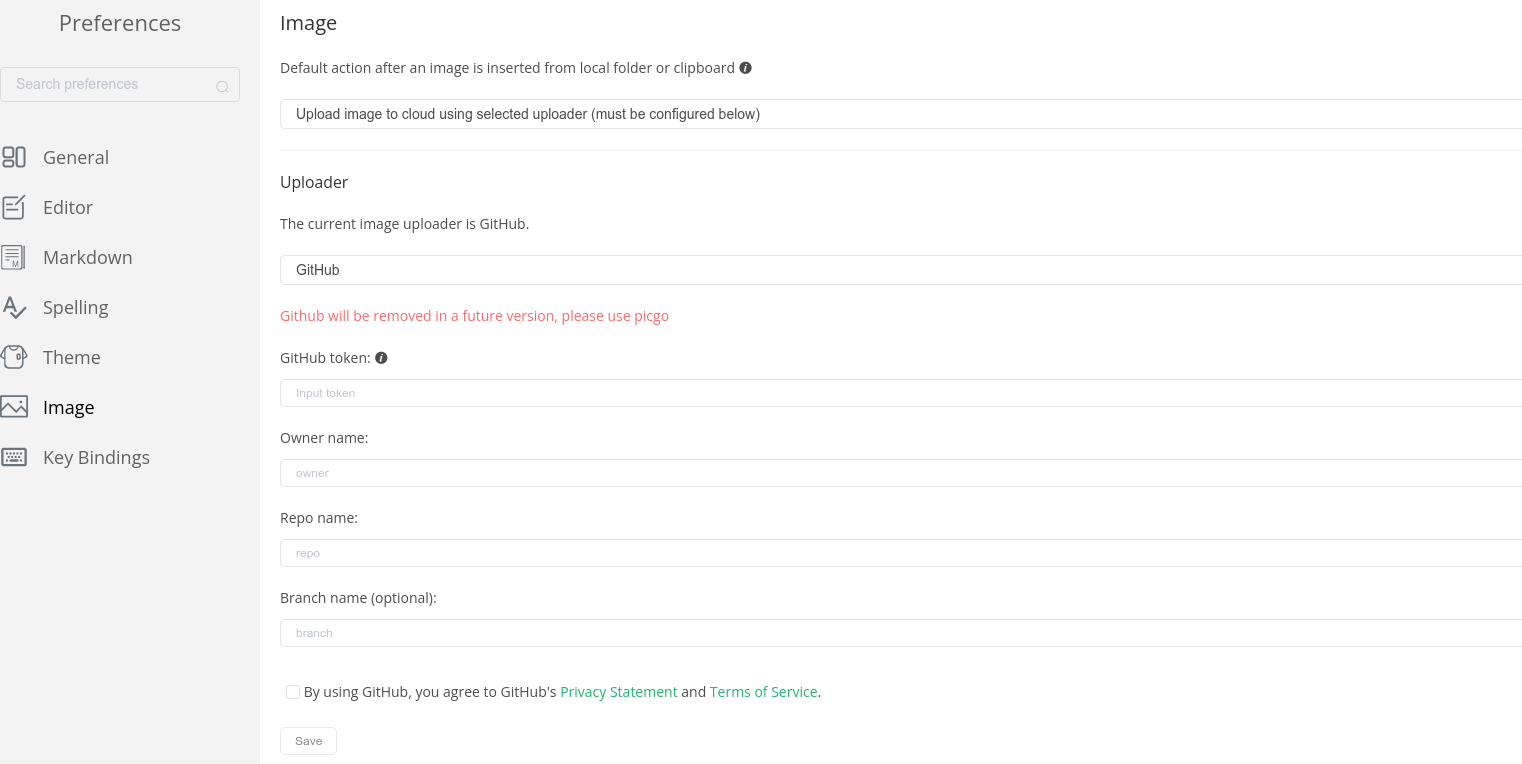

What it is WYSIWYG

Markdown editor modes refer to how you view and edit a document.

There are two main types: a raw editor and a WYSIWYG editor.

Raw Markdown Editor

In a raw markdown editor, you see and directly edit the plain text and its formatting symbols. For example, to make text bold, you have to type **bold text**.

The editor doesn’t hide the symbols; it displays them as you type.

Many developers and writers prefer this mode because it gives them full control over the syntax and is excellent for clean, distraction-free writing.

- Example: You type

## My Headingand see exactly## My Heading. The editor might add some syntax highlighting to color the##, but the symbols remain visible.

WYSIWYG Editor

WYSIWYG (an acronym for What You See Is What You Get) is a mode where the editor immediately renders the formatted text as you type.

It hides the Markdown symbols, so you don’t see the raw syntax.

For instance, when you type **bold text**, the editor will instantly display bold text with the two asterisks hidden.

This style is more intuitive for users who are not familiar with Markdown syntax and resembles a traditional word processor.

- Example: You type

## My Headingand as soon as you finish the line, it turns into a large, bold heading.

The Best of Both Worlds: Hybrid Editors

Many modern editors offer a hybrid approach.

These editors might start as a WYSIWYG editor but reveal the Markdown syntax when you click on or edit a specific line.

This allows for the speed of a visual editor while still giving you the ability to fine-tune the raw Markdown when needed.

Desktop markdown editors

For a notes 101 post… there are several desktop Markdown editors with WYSIWYG (What You See Is What You Get) capabilities beyond the previously mentioned apps.

These editors make editing Markdown more accessible by providing a live or in-place rendering experience:

Typora: A minimal and polished Markdown editor offering seamless WYSIWYG editing—what you type is rendered instantly, with syntax fading away as formatting is applied.[3][8]

APT method:

wget -qO - https://typora.io/linux/public-key.asc | sudo apt-key add -

sudo add-apt-repository 'deb https://typora.io/linux ./'

sudo apt update

sudo apt install typora- Snap method (if you prefer Snap packages):

sudo snap install typoraI liked typora, just that it doesnt bring a clear B/I/Image upload selector.

Zettlr: An open-source Markdown editor aimed at researchers and writers, offering in-place previewing and support for various Markdown enhancements.[3]

MarkText: A free, open-source Markdown editor that provides in-place previewing and an intuitive writing experience (cross-platform).

- AppImage (recommended for Ubuntu):

- Download the latest release from https://github.com/marktext/marktext/releases

- Make it executable and run:

wget https://github.com/marktext/marktext/releases/download/v0.17.1/marktext-x86_64.AppImage .

#cd /home/jalcocert/Applications

chmod +x /home/jalcocert/Applications/marktext*.AppImage

./marktext*.AppImage

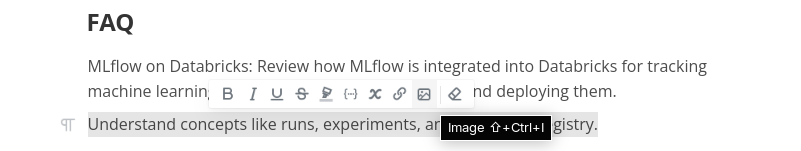

See also PicGo if you want to host images, or just use MarkText sync to Github

More about PicGo + MarkText 🚀

PicGo is an open-source, cross-platform tool designed to make image uploading to image hosting services (known as “pic-beds”) simple and fast, especially for people who write in Markdown.

It is highly popular among bloggers, developers, and writers who use static site generators or Markdown editors like Typora or VS Code, as it streamlines the process of getting images into their documents.

Core Functionality and Features

The main purpose of PicGo is to upload an image and automatically get the correct URL format (e.g., Markdown link) back to your clipboard.

- Clipboard Upload: You can copy an image to your clipboard (e.g., by taking a screenshot), and PicGo will upload it with a single click or keyboard shortcut.

- Drag-and-Drop: It supports dragging image files directly into the application window or a tray icon for instant upload.

- Automatic URL Copying: After a successful upload, PicGo automatically copies the image’s URL to your clipboard, formatted as a Markdown link (

), HTML, or another format you choose. - Cross-Platform: It is available as a desktop application for Windows, macOS, and Linux.

- Plugin System: This is a major strength. PicGo has a powerful plugin architecture that allows users to add support for various image hosts and implement image processing features like watermarking or compression.

Supported Image Hosts (Pic-Beds)

PicGo supports a wide array of hosting services, either natively or through its extensive plugin ecosystem:

| Native Support | Plugin-Based Support (Examples) |

|---|---|

| SM.MS (often the default) | GitHub/Gitee (common for free hosting) |

| Qiniu Cloud | Amazon S3 API (for AWS, MinIO, etc.) |

| Tencent Cloud COS | FTP/SFTP |

| Alibaba Cloud OSS | Cloudflare Images |

| UpYun | Nextcloud |

| Imgur | WebDAV |

PicGo-Core

In addition to the main desktop application, there is also PicGo-Core, which is the core logic and engine for image uploading.

- CLI & API: PicGo-Core provides both a Command Line Interface (CLI) and an API, allowing developers to integrate image uploading into scripts, other applications, or VS Code extensions (like the popular

vs-picgo). - Customization: It is the foundation upon which many of the advanced features and host integrations are built.

- Haroopad: Available on Windows, it supports advanced Markdown features and live preview with a WYSIWYG feel.[3]

- Texts: An editor designed for distraction-free writing, offering WYSIWYG Markdown editing, export, and PDF capabilities.[3]

- KeenWrite: Supports variable substitution, live preview, and Markdown WYSIWYG features (primarily Windows).[3]

See also Ghostwritter as seen here

sudo snap install alighieri

sudo add-apt-repository ppa:wereturtle/ppa

sudo apt update

sudo apt install ghostwriter

#sudo snap remove ghostwriterMost of these editors allow working directly with plain Markdown files, making them excellent choices for those who prefer a flat-file workflow coupled with a user-friendly editing interface.

DEB package:

- Download from https://www.zettlr.com/download

- Install via:

sudo dpkg -i ~/Downloads/Zettlr-*.deb sudo apt-get install -f

- Or use the AppImage as with MarkText:

chmod +x ~/Downloads/Zettlr*.AppImage ~/Downloads/Zettlr*.AppImage

DEB package:

- Download from https://pad.haroopress.com/user.html#downloads

- Install with:

sudo dpkg -i ~/Downloads/haroopad-*.deb

sudo apt-get install -fOutro

I was thinking to open to the public my nextcloud app and put TinyAuth on top of it.

In that way I could sync the LogSeq markdown notes between my devices.

But its not that easy when I thought on how the authentication works for mobile apps.

TinyAuth and Nextcloud Android App

This is an excellent question and it’s a critical point to understand when self-hosting and trying to integrate with mobile apps.

The short answer is: Yes, the same problem exists with Authelia, Okta, and most other external identity providers, but the solution is different.

TinyAuth is a simple “forward auth” proxy.

It just redirects the user to a basic login page.

More sophisticated identity providers like Authelia and Okta use a standard known as OpenID Connect (OIDC).

The Problem with “Forward Auth” Proxies

The issue you had with TinyAuth is fundamental to how “forward auth” works.

Back in spring, I had pending to explore further what FAuth is…here we are

The reverse proxy intercepts every request and says, “Nope, you have to log in first.”

Mobile apps don’t understand this redirection; they just expect to talk directly to the server’s API endpoints.

Since they can’t handle the redirect to the login page, the authentication fails.

The Solution: Using OpenID Connect (OIDC)

Instead of using a forward auth proxy, Nextcloud and other modern web applications are designed to integrate directly with external identity providers (IdPs) using protocols like OpenID Connect (OIDC) or SAML.

Here’s how this changes the authentication flow:

- Nextcloud handles the authentication: You install the Nextcloud “OpenID Connect user back-end” app (or “Social Login” app) from the Nextcloud app store.

- Redirect to the IdP: When a user clicks “Log in with Authelia” on the Nextcloud web login page, Nextcloud generates an authentication request and redirects the user’s browser to the Authelia server.

- Authentication and Redirection: The user authenticates with Authelia (e.g., enters username/password, completes 2FA). After a successful login, Authelia sends the user back to Nextcloud with a special token.

- Token Exchange: Nextcloud receives this token, verifies it with Authelia, and then creates a user session for the authenticated user.

This approach works great for web browsers because they are designed to handle redirects.

What about the Mobile App?

The Nextcloud Android app cannot perform the full OIDC redirect flow itself.

It also doesn’t know how to talk to Authelia directly.

So, how does it authenticate?

The Nextcloud mobile app is specifically built to use Nextcloud’s built-in authentication mechanisms, even when an external IdP is in use.

There are two primary ways it can do this:

Nextcloud’s “App Passwords”: This is the most common method. You log in to Nextcloud via the browser (authenticating with Authelia first), and then go to your user settings to generate an “app password.” This password is a long, randomly generated string that is unique to the device and bypasses the external IdP. The mobile app then uses this app password to authenticate directly against the Nextcloud server.

OIDC Mobile App Flow (Less Common): Some identity providers and apps are beginning to support a more modern OIDC flow specifically for native mobile apps. This involves a browser-like view opening within the app, completing the OIDC flow, and then passing the token back to the app. While this is the future, it’s not the default or most common approach with Nextcloud right now, and support for it can be hit-or-miss depending on the specific combination of Nextcloud, the mobile app, and the IdP.

So, to summarize:

- TinyAuth-style “forward auth” breaks mobile apps because they don’t understand the redirection.

- Nextcloud can work with OIDC providers like Authelia and Okta, but it does so by managing the authentication flow itself and redirecting the browser.

- The Nextcloud mobile app typically does not use the OIDC flow. It relies on either a username/password combination or, more securely, a special app password that is generated within Nextcloud after you have authenticated via the web.

Therefore, regardless of whether you use TinyAuth, Authelia, or Okta, the solution for the Nextcloud Android app remains the same: use an app password.

This is the intended and most reliable way for third-party clients to connect to your Nextcloud instance when external authentication is enabled.